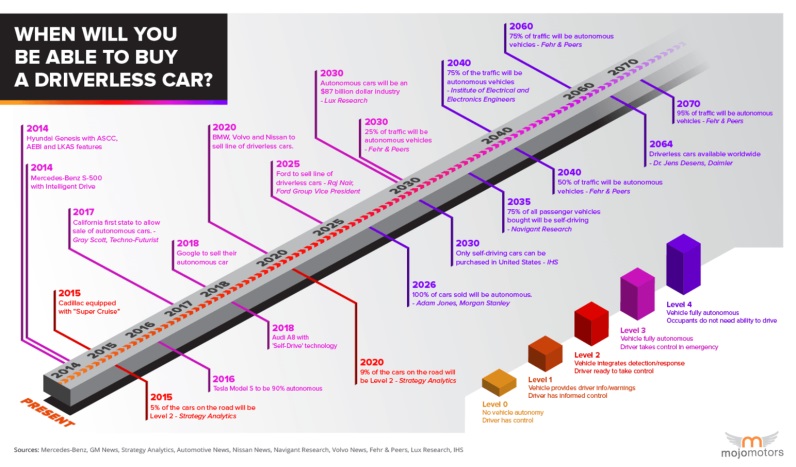

Expected Timeline

Long-Term Predictions

The timeline for the introduction, adoption, and widespread use of fully-automated vehicles (AVs) is still largely unknown due to public opinion, policy boundaries, and current technological development. Below are some prevailing predictions for long-term adoption of self-driving vehicles.

Source: Mojomotors, 2014

Source: Mojomotors, 2014

The graph below shows a more recent AV deployment timeline. Source: Twitter

Source: Twitter

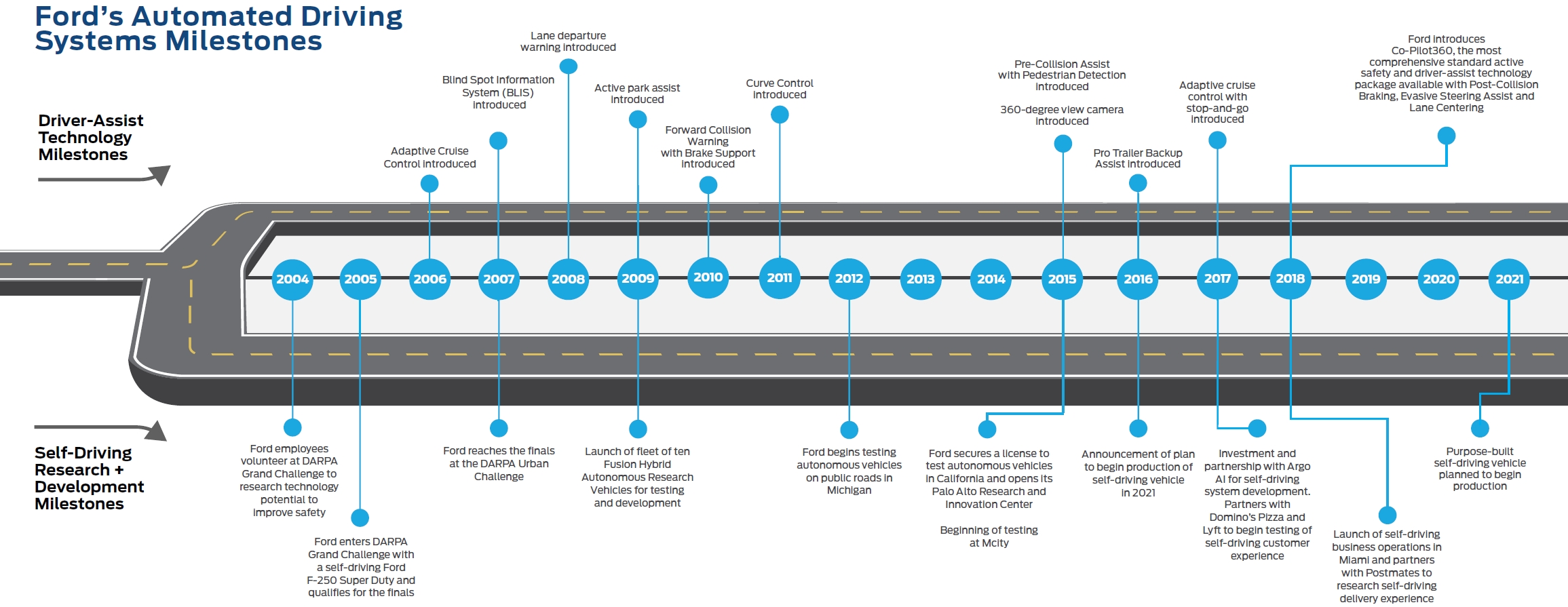

Further, Ford Motor Company also published a report showing its development timeline.

Automakers’ Projections

With the recent release of Google’s first self-driving car and Tesla’s autopilot software, other automakers are eager to join the AV market.

- General Motors plans to mass-produce self-driving cars that lack traditional controls like steering wheels and pedals by 2019 (Hawkins, 2018)

- Honda intends to reach level 3 autonomy by 2020 and level 4 by 2025 (Byford, 2017)

- BMW is slated to release the iNEXT in 2021, which will have level 5 autonomy capabilities (Boeriu, 2017)

- Other projections can be found at Venture Beat (Fagella, 2017)

The Ford Motor Company plan to have AVs ready for market in 2021, when their level 4 AVs could operate without a steering wheel or brake pedals. In the past two decades, they designed and tested the driver-assist technology and automated driving technology to improve safety and reliability, so as to provide valuable customers’ experience. The company is working on an on-demand delivery platform in Miami and Miami beach with the participation of 70 local businesses and using Ford Fusion Hybrid sedans fleet tested on public roads in Miami, Pittsburgh, and Dearborn. In the future, they would also test AVs for serving police and heavy-duty service fleets, as well as testing hybrid-electric technology to AVs (Ford Motor Company, 2018).

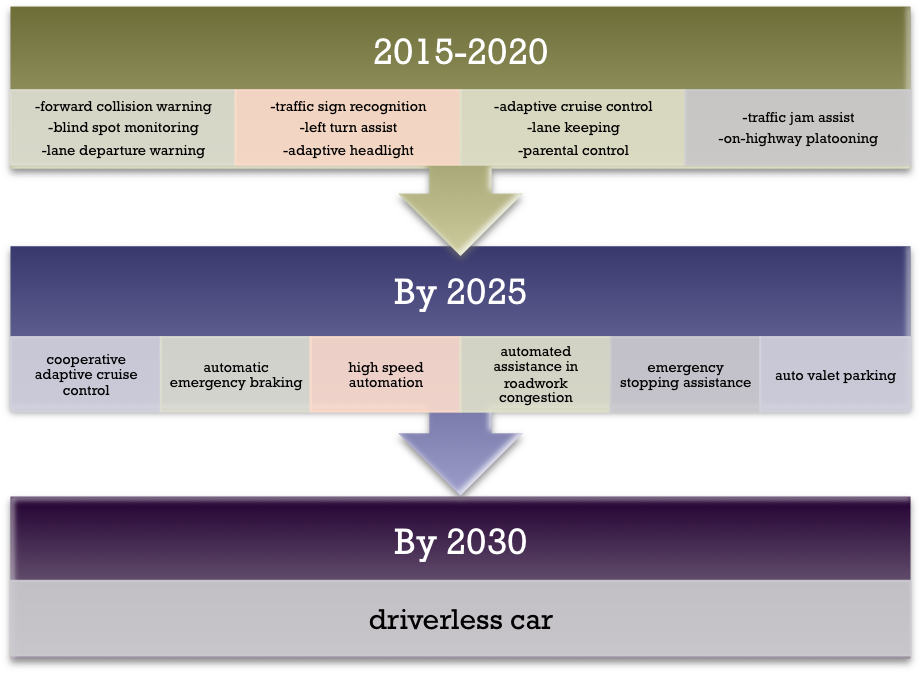

Technology Development Timeline

In recent years, there have been major strides in the technology developments toward autonomy. Dr. Sven Beiker, the managing director of Silicon Valley Mobility, summarized the technologies that have been achieved so far at a Samsung forum. Source: Beiker, 2018

Source: Beiker, 2018

Based on a study conducted by the Center for Transportation Research at the University of Texas at Austin from 2015-2016, the forecast for technology development leading to self-driving cars is summarized below.  Source: Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 22

Source: Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 22

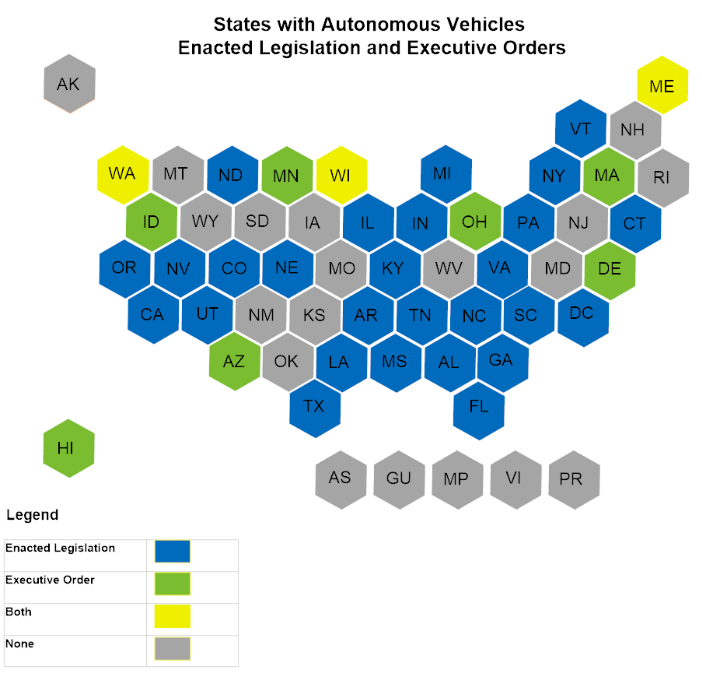

Policy and Legislation Timeline

Each US state is responsible for its own AV driving legislation. Nevada was the first state to authorize the operation of AVs in 2011. Since then, 21 other states have passed legislation related to AVs. In 2017, 33 states had either passed legislation, issued executive orders, or announced initiatives to accommodate AVs on public roads. California is undoubtedly the top-ranked state in openness and preparedness for AVs. Its AV testing regulations were introduced in September 2014 and required a driver be in the vehicle, ready to assume control. Recently, California took a step forward by allowing AVs with no driver to operate on its public roads (Peng, 2018).

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL, 2018) has a new AV legislative database, providing up-to-date, real-time information about state AV legislation that has been introduced in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Americans’ Long-Term Adoption

A large hurdle that developers of AVs will have to overcome is getting drivers as well as the riders on board with the idea of an AV. This must be done by convincing people that AVs are safer than conventional vehicles and that they can be trusted. The level of public acceptance for the technology will largely determine the adoption rate of AVs, despite the rate at which the actual technology is developed. That is, even if automakers put vehicles into the market, AVs will not become widespread unless the general population trusts the technology.

According to recent surveys, Americans are still hesitant to accept the technology as a norm. Through survey data about Americans’ willingness to pay for the different levels of automation as well as simulations based on various price reductions, Prateek Bansal finds that “without a rise in people’s Willingness to pay (WTP), or policies that promote technologies, or rapid reductions in technology costs, it is unlikely that the U.S. light-duty vehicle fleet’s technology mix will be anywhere near homogeneous by the year 2045,” (Bansal and Kockelman, 2017). This indicates a need to further educate the general public about the potential benefits that AVs could bring.

Through another simulation calibrated by the results of a survey of Americans, Neil Quarles, an active transportation and street design graduate engineer from the Transportation Department of City of Austin, finds that: “the availability of an option to retain human-driving capabilities in AVs has a noticeable effect on their level of adoption and their share of total VMT, due to the higher WTP that exists for AVs if they include that human-driven option,” (Quarles and Kockelman, 2018). This indicates that people are willing to accept self-driving cars for the convenience, but they are not willing to completely give up their independence when it comes to owning and driving their own vehicles. Policymakers will then need to determine whether the advantages of accelerated adoption of AVs, given the presence of the human-driving feature, outweighs the safety disadvantages associated with allowing people to continue driving.

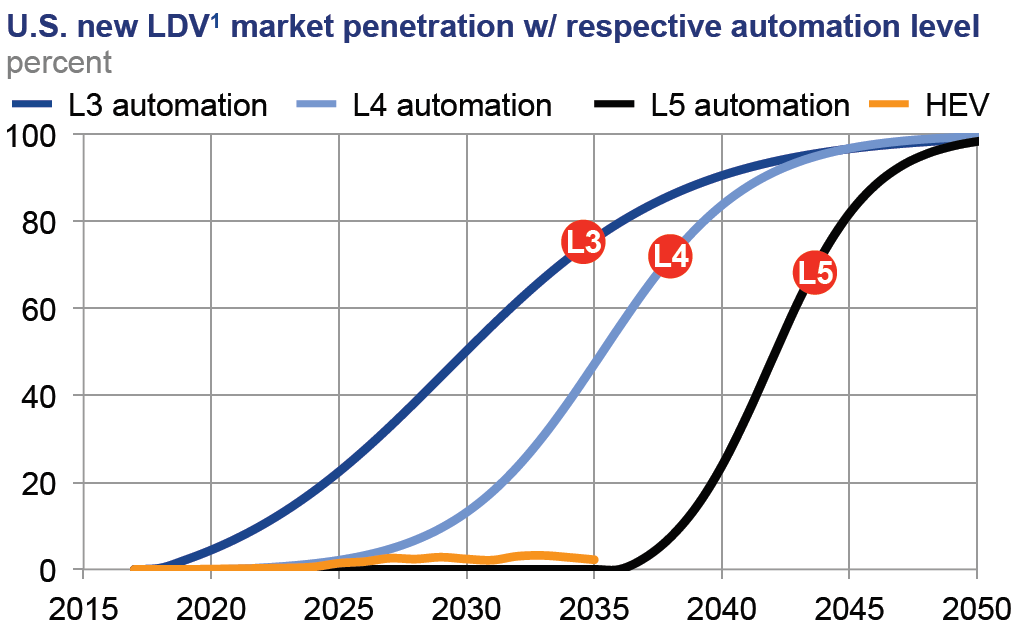

According to Dr. Sven Beiker, Level 3 automation had a soft launch in 2017 with the release of the Audi A8 and Tesla Autopilot and followed a “convenience” curve. Based on the below image, Level 4 automation starts in autonomous ride-sharing around 2020 but has relatively slow market adoption initially. Level 5 not expected before 2035, but upon implementation, very fast market adoption is expected.

Source: Beiker, 2018

Source: Beiker, 2018