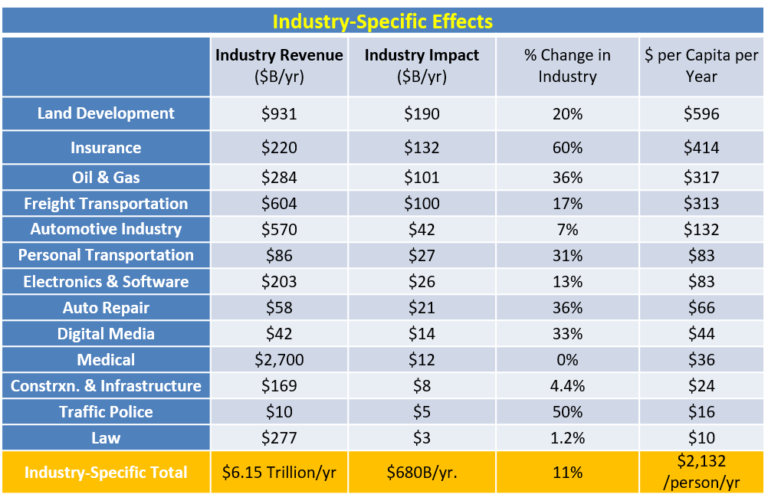

Industry Impacts

A study led by Dr. Kara Kockelman of UT Austin examined the impacts of AVs on the US economy and industry, shown below.

Source: Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 327

AVs allow travelers to perform different tasks while commuting. The time drivers save from freeing their hands can be used for reading, sleeping, online shopping, etc. The decreased value of travel time (VOTT), or the driver’s willingness to pay to save time, ensures increased work productivity. AVs will ease mobility for disabled persons who would otherwise not be able to drive. This improved accessibility will have positive impacts on the economy. With safety being the most important factor in choosing AVs, they will bring the greatest benefits to industries related to safety services. For example, legal, fuel, administration, and insurance companies will face negative consequences. In contrast, the automotive industry will see the biggest improvements.

Automotive Industry

People and businesses are likely to use Mobility as a Service (MaaS) instead of owning cars. With the convenience of travel modes and reduced time travel, personal vehicle ownership is expected to decline. With AVs and electric vehicles (EVs) forthcoming, we can expect more manufacturers and technology providers for these vehicles. Clements and Kockelman, 2017 predict that software will eventually make up a larger value in a vehicle than the hardware.

Freight-related Impacts

Heavy commercial trucks and freight are likely to be some of the first vehicles to implement autonomous technology. Given the economic viability of fleet implementation for freights and its high efficiency, this industry will benefit from AV technology. McKinsey estimates that the economic gains of driver-less vehicles in the trucking industry could be range from $100-500 billion per year by 2025 (McKinsey, 2013). The bulk of these savings would come from the elimination of the wages of the truck drivers.

Clements and Kockelman also note, “after assistive systems, fully automated vehicles will allow convoying, in which the lead driver of a chain of multiple trucks is in control of driving, but the following trucks require no human input and are connected wirelessly to the lead truck. Convoy systems would allow long-distance drives with large quantities of goods and avoid many driver-based hours-of-service restrictions,” (Clements and Kockelman, 2017 p. 6).

Personal Travel

AVs reduce the VOTT, which is defined as the willingness to pay (WTP) to avoid an hour of travel. If one is able to make more productive and less stressful use of travel, by becoming a passenger, rather than a driver, his/her VOTT falls. This makes CAVs relatively attractive for current drivers, if not for current passengers (Kockelman et al., 2017, p. 9). Given the high cost of personal AVs, they are likely to be viewed as luxury items and be owned by only a privileged few.

Collisions

Based on the results of a study, CV technologies, including V2V (vehicle-to-vehicle), V2I (vehicle-to-infrastructure), and V2P (vehicle-to-pedestrians), are estimated to save between $23 billion and $28 billion in economic costs each year, and as much as $96 billion to $117 billion in comprehensive costs each year in the U.S. (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 190).

Infrastructure

As a 2016 study sponsored by the Texas Department of Transportation notes, “when vehicles become fully automated, there may no longer be a need for extra-wide lanes, guardrails, traffic control signals, wide shoulder, or rumble strips among other safety measures because of increased safety, and manufacturers of these components will lose a source of income” (Kockelman et al., 2016 p. 322-323). It is also likely to transform existing parking systems. Infrastructure deployment in the public realm will incur high initial investments.

Land Development

AVs may be able to mitigate the overcrowding problem but, on the other hand, planners may face issues of unexpected urban sprawl in the future. The space freed up by unnecessary parking space and/or garages can be used innovatively for other purposes using design thinking.

Medical Industry

The medical industry is also likely to lose business from the improved safety of CAVs. “McKinsey & Co. (2013) estimated that the combination of auto repair and health care bills could save consumers $180 billion, which would generate proportional losses for service providers” (Clements and Kockelman, 2017 p. 8).

Insurance Industry

Reductions in crash frequency will also affect insurance companies, “safety improvements as a result of AVs will require insurance agencies to adapt and possibly reconstruct their fundamental business models. Insurance agencies currently net $180 billion annually in the U.S. insuring against automobile accidents and the related medical costs” (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 321). However, in the case of a crash, whether the vehicle owner or the hardware and software manufacturers are liable remains ambiguous.

Oil and Gas Industry

The implementation of automated driving systems may improve fuel efficiency, “the decreased need for parking will improve fuel efficiency, as one MIT study found that 40% of total gasoline use in cars in urban areas is spent looking for parking (Diamandis 2014). SAV fleets could make electric vehicles a more viable option and even financially preferable for fleet management companies. All of these factors suggest that drivers would demand less gas for their cars” (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 12).

Labor Industry

Automation of the driving task may bring negative impacts to the labor industry. According to the American Trucking Association (2015), the industry employs over 3 million truck drivers and the automation of driving poses a huge threat to the livelihood of these truck drivers. At this time, however, there is already a shortage of about 25,000 truck drivers because of the long hours and time away from home (American Trucking Association, 2015). AVs may also put a strain on unemployment benefits currently offered by the federal government (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 319).

Shared (Fully) Automated Vehicles

SAVs are economical for fleet ownership with public and private rented or shared fleets seeing a rise due to the cost competitiveness. A high penetration rate of SAVs can lead to social issues like unemployment in certain sectors such as drivers or motor technicians.

Assumptions for Valuation of AVs at 10%, 50% and 90% Adoption Rates

(Fagnant and Kockelman, 2016)

Safety

- 50%, 75%, and 90% per-AV crash reductions

- ½ benefits for pedestrians and bikes, ¼ benefits for motorcycles

Congestion

- 15%, 35%, and 60% freeway delay reductions

- 5%, 10%, and 15% surface street delay reductions

Other Assumptions

- 10% of all new AVs are shared (serving 10x as many trips)

- 250 workdays per year, with $1/day parking savings

- 20%, 15%, and 10% per-AV vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) increases

Conclusions

- Though many potential benefits are still speculative, “assuming that CAVs eventually capture a large share of the automotive market, they will have major economic impacts, on the order of $4,900 per American per year” (Kockelman et al., 2016, p.12)

- The number of vehicles purchased each year may fall, due to vehicle sharing within families and across household members or through shared fleets, but rising travel distances and a shift away from air travel may lead to greater vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) and ultimately higher vehicle sales (due to faster fleet turnover from heavy daily use).

- Owing to affordability and efficiency, heavy commercial trucks may be the first industry to implement AV technology in order to increase efficiency, with “the ideas of automated freight and transit [being] attractive for potential affordability and reliability. However, when job losses are mentioned, concerns are raised about negative economic effects” (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 94).

- Personal transport may shift toward shared (fully) automated vehicle fleet use, threatening the business of taxis, buses, and other forms of public transport.

- Fewer collisions and more law-abiding vehicles, due to smarter, automated vehicle operations, will lower demand for auto repairs, traffic police, medical assistance, insurance, and legal services (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 12).

- Electrification of a SAV fleet is not yet financially advantageous.

- The shifts in the supply and demand curve will reflect a new economy which is generated by economies of scale, new markets and new products/services (Mudge, 2014).

- The prospects of IT workers and analysts are positive as we enter this automation age. The evolution of Mobility as a Service companies in the passenger economy will create businesses that are all about the data (Lanctot, 2017 p. 10). Data analysts will become increasingly important as self-driving cars collect data about every single aspect of our day. These data could be worth up to US $750 million by 2030 (Alexiou, 2017).