Automated Vehicle Policy

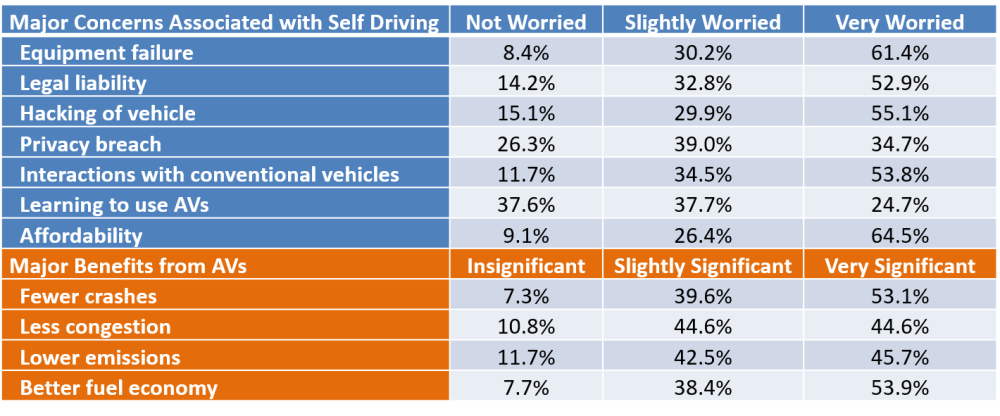

Survey results for Texans, shown below, enumerate their attitudes toward self-driving vehicles. Such surveys can help shape the policies for the region.

Source: (Bansal and Kockelman, 2017)

Public Policy Imperatives for AVs

Source: (KPMG, 2016)

Existing Policy

The USDOT does not currently have a comprehensive plan outlining the overall goals or a plan to monitor progress. The DOT recently formed a group to lead policy development in the future but has not announced a detailed time frame or scope of work. The NHTSA’s Federal Automated Vehicles Policy (FAVP), issued on September 20, 2016, represents a significant step in the development of a federal regulatory framework to guide the development of automated vehicle technologies (Malley and Reindl, 2016). The FAVP is a comprehensive document, over 100 pages in length, addressing many facets of the regulation of automated vehicles (NHTSA, 2016). The policy consists of four parts.

Part 1: Vehicle Performance Guidance for Automated Vehicles. It has the greatest practical significance because it sets forth a “Safety Assessment” that manufacturers are expected to perform prior to the testing or deployment of automated vehicles on public roads.

Part 2: Model State Policy for Automated Vehicles. In general, the federal government (through the NHTSA) regulates the safety of the vehicles themselves, while state governments regulate the use of the vehicles via registration, licensing of drivers and operation.

Part 3: NHTSA’s Current Regulatory Tools. Summarizes existing NHTSA regulatory authorities and describes how those authorities can be applied to address the introduction of automated vehicle systems.

Part 4: Potential New NHTSA Regulatory Tools. NHTSA identifies a range of potential new regulatory tools that could be adopted, recognizing that its existing tools may not be well-suited to the rapid pace of innovation in automated vehicle technologies.

NHTSA encourages collaboration and communication between State, Federal and local governments and the private sector as AV technology develops (Transpogroup, 2017; AV America, 2018). For topics like equity, VMT, technology, land use, safety, GHG, and goods, movement and services, “NHTSA has the authority to identify safety defects, allowing the Agency to recall vehicles or equipment that pose an unreasonable risk to safety even when there is no applicable Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS)” (NHTSA, 2016 p.7). Furthermore, “in 2016, NHTSA adopted the SAE J3016 definitions as their standard. These were issued as policy and not regulations. States retain their responsibilities for vehicle licensing, registration, traffic laws and enforcement and motor vehicle insurance and liability. NHTSA continued preemption for interpretations, exemptions, notice, and rulemaking and enforcement authority. Manufacturer responsibility to determine their system according to SAE J3016 standard” (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2017).

Policy Principles for AVs

Policies regarding AVs must inform the following topics (APA, 2018).

- Mobility, connectivity, access

- Social and environmental equity

- Energy, sustainability, and research & development

- Safety and security

- Data and decision making

- Economics and fiscal planning

Liability

A vehicle driven by a computer on public roads opens the possibility of many insurance and liability issues. California law (CIS 2013) requires 30 seconds of sensor data storage prior to a collision to help establish fault, assuming that the AV has been programmed and tested properly (Kockelman et al., 2016). Liability, security, and privacy concerns represent substantial barriers to widespread AV technology implementation. These issues should be addressed through regulations to give manufacturers and investors more certainty in development, as “without clear legal language saying otherwise, the person using the AV is still considered the driver and would have the same legal obligations as any other driver in the state,” (CSG, 2016, p. 5). Liability standards should strike the balance between assigning responsibilities to manufacturers without putting undue pressure on their product (Fagnant and Kockelman, 2015, p. 16).

Empty VMT

Travel demand simulation results suggest that traveler behaviors will change significantly once AVs are available. Over 60% of CAV owners would prefer empty repositioning to on-site parking, in order to avoid parking costs. However, empty repositioning adds empty VMT (vehicle-miles traveled) to the network and makes transit use less attractive (Liu et al., 2017). Consequently, the TxDOT, cities, and counties should consider constraints on all empty-vehicle travel, unless it is by an operator managed fleet that is held to a maximum share of VMT driven empty (e.g., 10 percent, with lines for additional empty driving) and time- and location dependent (congestion-based) road pricing should be adopted, using the GPS, DSRC or 5G communication technology that connected vehicles require. SAVs will bring rather dramatic changes in vehicle ownership and travel patterns. They can add large numbers of empty, but relatively short, repositioning trips to reach the next travelers (Kockelman et al., 2016, p. 2).

Credit-Based Congestion Pricing

Credit-based congestion pricing (CBCP) can be a novel strategy proposed as a policy. A revenue-neutral policy where road tolls are based on the negative externalities associated with driving under congested conditions, its generated tolls are returned to all licensed drivers in a uniform fashion, as a sort of driving “allowance.” Essentially, the “average” driver pays nothing, while frequent long-distance peak-period drivers subsidize others, in effect paying them to stay off congested roads (Kockelman and Kalmanje, 2005, p. 1).

Privacy

Privacy is a major concern with the storage of data. Below are various recommendations for cybersecurity (NHTSA, 2016, p. 19).

Transparency: Provide consumers with accessible, clear, meaningful data privacy and security notices/agreements which should incorporate the baseline protections outlined in the White House Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights and explain how Entities collect, use, share, secure, audit, and destroy data generated by, or retrieved from, their vehicles

Choice: Offer vehicle owners choices regarding the collection, use, sharing, retention, and deconstruction of data, including geolocation, biometric, and driver behavior data that could be reasonably linkable to them personally

Minimization, De-Identification and Retention: Collect and retain only for as long as necessary the minimum amount of personal data required to achieve legitimate business purposes, and take steps to de-identify sensitive data where practical, in accordance with applicable data privacy notices/agreements and principles

Data Security: Implement measures to protect data that are commensurate with the harm that would result from loss or unauthorized disclosure of the data

Integrity and Access: Implement measures to maintain the accuracy of personal data and permit vehicle operators and owners to review and correct such information when it is collected in a way that directly or reasonably links the data to a specific vehicle or person

Accountability: Take reasonable steps, through such activities as evaluation and auditing of privacy and data protections in its approach and practices, to ensure that the entities that collect or receive consumers’ data comply with applicable data privacy and security agreements/notices

As the NHTSA notes, “manufacturers and other entities should have a documented process for testing, validation, and collection of event, incident, and crash data, for the purposes of recording the occurrence of malfunctions, degradation, or failures in a way that can be used to establish the cause of any such issues,” (NHTSA, 2016, p. 17).

Leadership

Texas’ leadership in CAV testing allows it to play a leading role in influencing the development of the technology. Recommendations, including short-term, mid-term and long-term practices for shaping legislative policy on CAVs, position Texas as a national leader in using the market to encourage even smarter technological innovation (Kockelman et al., 2016).

Licensing

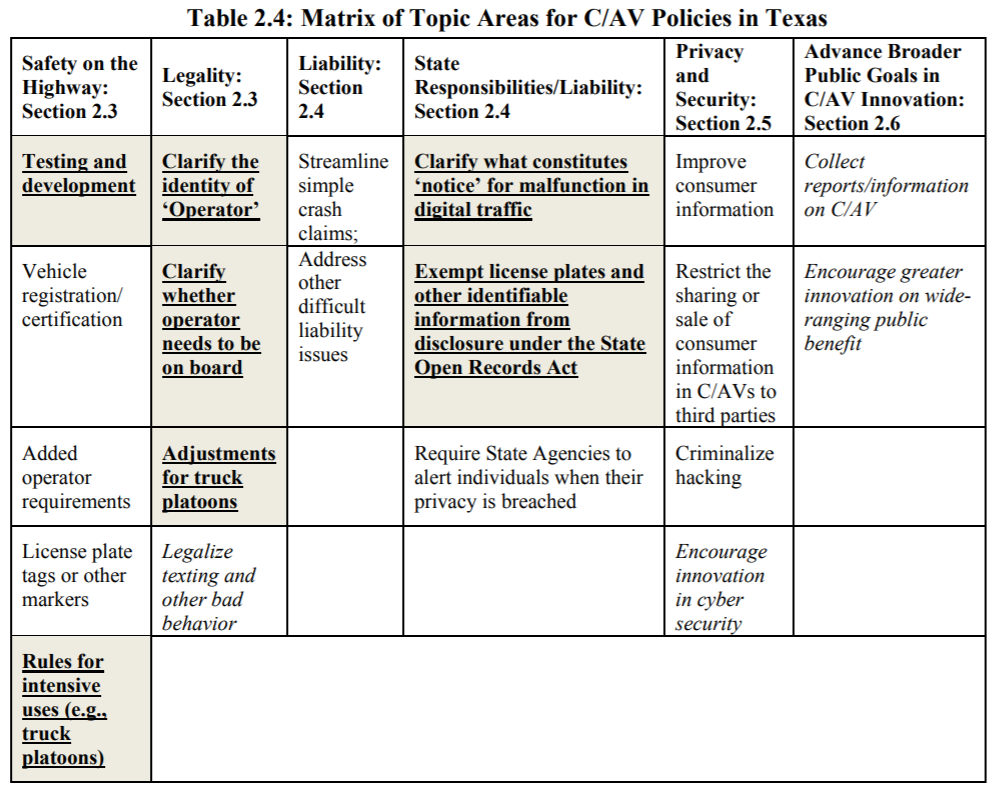

Source: (Kockelman et al., 2016 p. 66)

As noted in the legal section of a 2016 study sponsored by the TxDOT, “the speed and nature of the transition to a largely AV system are far from guaranteed; they will depend heavily on purchase costs, as well as licensing and liability requirements. Nevada has already processed AV testing licenses (on public roads) for Google, Continental, and Audi, subject to certain geographic and/or environmental limitations (e.g., the autonomous operation only on the state’s interstates, for daytime driving free of snow and ice). On February 26, 2018, the Office of Administrative Law of California approved the driverless testing regulations. Both licensing requirements from California and Nevada include a minimum of 10,000 autonomously driven miles and documentation of vehicle operations in a number of complex situations” (Kockelman et al., 2016).

Vehicle Registration

Nevada’s legislation contains 23 lines of definitions and broad guidance to its DMV, while California’s is more detailed and with specific direction to their DMV (to establish safety and testing specifications and requirements). Without a consistent (or at least congruent) licensing framework and safety standardization for acceptance, AV manufacturers may face regulatory uncertainty and unnecessary overlap (Fagnant and Kockelman, 2015, p. 12).

Initial Issues, Challenges, Questions

Legal articles have primarily focused on privacy, liability, cyber security & constitutional protections. State open records request that these issues, on which there are no case law yet, are all raised as concerns for AVs.

NHTSA & FTC have noted they are reviewing hacking and privacy of consumer data in HAVs. Federal statutes also provide penalties under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, Digital Millennium Copyright Act, Wiretap Act, and Patriot Act.

In the privacy realm, three areas have been identified as needing changes to law (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2017, slide 47).

- Autonomy privacy, or an individual’s privacy under Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (e.g., illegal search & seizure);

- Personal information privacy, and

- Surveillance

Specific Recommendations for TxDOT Headquarters and Divisions

Near-term (through 2021)

- Road markings to facilitate lane departure warning, traffic jam assist and platooning

- Signage development for CAVs that detects and interprets road signs

Mid-term (2021-2031)

- Construction/detours for re-routing CAVs when needed

- Lane management, including the introduction of CAV-only lanes on freeways and city streets

- Nighttime rules of the road for CAVs

- SAV integration for facilitating optimal operation

- Developing and enforcing regulations of empty driving

- Roadway design amendments to incorporate CAV design requirements

- Tolling and demand management for alternative revenue generation and congestion control

Long-term (2031 and beyond)

- Construction & maintenance design pertaining to construction automation, incident response, etc.

- Rural signage & rural road design to transition CAVs from urban environments

- Smart intersections allowing for a greater level of optimization than is possible with existing traffic signals.

Others

- Charge users for miles traveled in state. Incentivize less congested routes. This will encourage users to choose routes based on value of personal time. Empty driving should be prohibited or strongly limited (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2017).

- Regulations for vehicle inspections to audit malfunctioning devices. Regulations to monitor the technological advances.

- State should work with MPOs and consultants to adopt agent-based models of travel demand and traffic (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2017).

- “Policies for smarter system management, including incentives for ride-sharing and non-motorized travel, route guidance and credit-based congestion pricing” (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2017).

- Each state should have a CAV policy to encourage general adoption. Pilot programs are preferable (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2017).

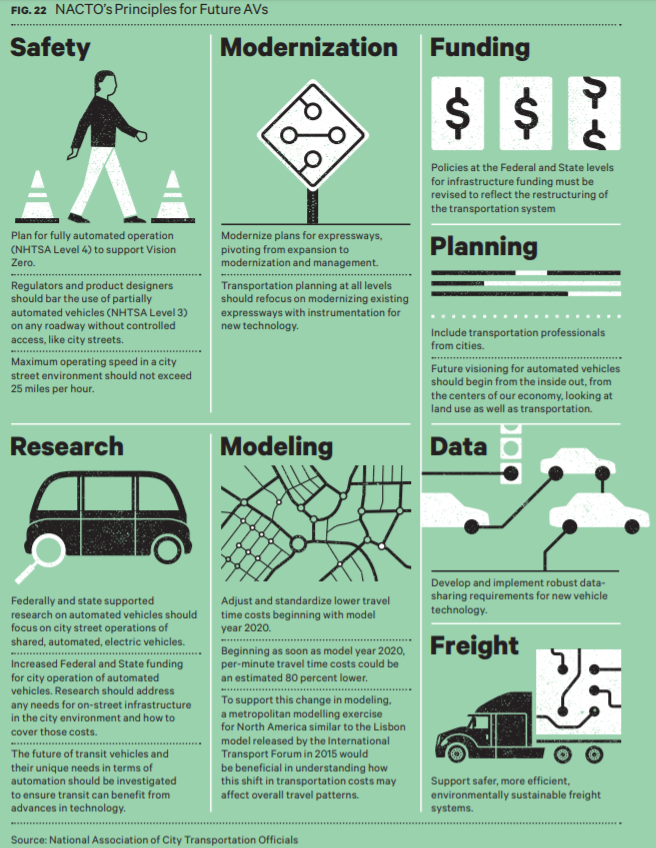

- Modernize traffic data. “Develop and implement robust data-sharing requirements for new vehicle technology to improve the quantity and quality of data collected, and to reduce the millions of dollars spent annually on technologically primitive data collection, both from regular traffic operation and from traffic crashes” (NACTO, 2016, p. 2).

- “APA supports efforts to eliminate or sharply reduce municipal and off-street parking requirements with the growing incorporation of AVs into the national transportation system and permit the reuse of parking structures as active land uses” (APA, 2018, p. 2).

- “To produce more consistency in the protection of privacy, the legislature could limit the private information on citizens that must be disclosed through the Open Records Act.” (Kockelman and Loftus-Otway, 2016)